Keeping Memories Alive

My Terezin Diary, a Memoir, by Zuzana Justman

I kept the diary from December 8, 1943, until March 4, 1944—the first winter of the two years I was imprisoned with my parents, Viktor Pick and Marie Picková, and my brother, Bobby, in the Czech concentration camp. (The camp was also known as Theresienstadt.) In addition to eight entries, it contains a few drawings, a poem about snow, and a story dealing with Terezín morality. Right after the war, I added a list of my girlfriends, marking the names of those who did not survive with a minus sign. When I first returned to the diary, many years ago, I found it difficult to read. Zuzana Justman, born Zuzana Pick, is a Czech-American maker of documentary films and writer. She was born in former Czechoslovakia. After surviving two years at Theresienstadt concentration camp during World War II she, her mother, and brother returned to Prague. Following the communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948, she and her mother emigrated to Argentina.

In 1950 Zuzana moved to the United States to pursue undergraduate and graduate education. After working as a writer and translator, in the late 1980s, she started filmmaking. She has filmed most of her documentaries in the Czech Republic and other European countries, and her topics have been the Holocaust of World War II and postwar history.

Her story My Terezin Diary was published in The New Yorker on September 9, 2019. It was also published in German translation in Switzerland in Das Magazin in January 2020.

Personal History September 16, 2019 Issue

My Terezín Diary

What is most striking to me today about the diary I kept in the camp, seventy-five years ago, is what I left out.

By Zuzana Justman

On a freezing day in January, 1944, after my family and I had been confined at Terezín for six months, my mother was arrested by the S.S. and placed in a basement cell in the dreaded prison at their camp headquarters. Not even her lover, who was a member of the Terezín Aeltestenrat, or Council of Elders—the Jewish governing body—could get her released.I was twelve years old, and I was afraid that I would never see her again. But on February 21, 1944, all I wrote in my diary was “Mommy was away from us.”What is most striking to me today about the diary I kept seventy-five years ago is what I left out.

I kept the diary from December 8, 1943, until March 4, 1944—the first winter of the two years I was imprisoned with my parents, Viktor Pick and Marie Picková, and my brother, Bobby, in the Czech concentration camp. (The camp was also known as Theresienstadt.) In addition to eight entries, it contains a few drawings, a poem about snow, and a story dealing with Terezín morality. Right after the war, I added a list of my girlfriends, marking the names of those who did not survive with a minus sign.

When I first returned to the diary, many years ago, I found it difficult to read. Picking up the small book, three inches by four inches, with its cover of frayed green leather and its entries in tiny writing, I was not ready to be reminded of that terrible first winter in Terezín. I did not have much patience with my childish pronouncements (“Now I see, though, that it is possible to find happiness in work and in other things”) and my determined attempts to look at the bright side (“It will get better with time”).I put the diary away, and then for a long time I could not remember where I had hidden it. It was only a few years ago that I finally discovered it, on a high shelf of my closet, and, to my surprise, I saw it in a new light.

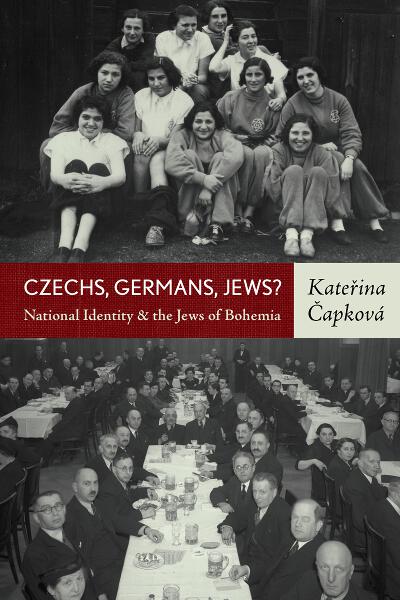

Czechs, Germans, Jews? Exploring national identity among Jews of Bohemia.

Czechs, Germans, Jews? National Identity & the Jews of Bohemia, by Kateřina Čapková, published by Berghahn, 2012.

The phenomenon of national identities, always a key issue in the modern history of Bohemian Jewry, was particularly complex because of the marginal differences that existed between the available choices. Considerable overlap was evident in the programs of the various national movements and it was possible to change one’s national identity or even to opt for more than one such identity without necessarily experiencing any far-reaching consequences in everyday life.

Based on hitherto unknown archival sources from the Czech Republic, Israel and Austria, SHCSJ’s board member, Kateřina Čapková’s 2012 book reveals the inner dynamic of each of the national movements and maps out the three most important constructions of national identity within Bohemian Jewry – the German-Jewish, the Czech-Jewish and the Zionist. This book provides a needed framework for understanding the rich history of German- and Czech-Jewish politics and culture in Bohemia and is a notable contribution to the historiography of Bohemian, Czechoslovak and central European Jewry.

Kateřina Čapková is a board member of the Society for the History of Czechslovak Jews, and a research fellow at the Institute of Contemporary History, Prague. She teaches Modern Jewish History at Charles University and NYU in Prague. With Michal Frankl she is the co-author of Nejisté útočiště, a book about Czechoslovakia and refugees from Nazi Germany (2008, in German 2012).

Find out more at: www.berghahnbooks.com/title/CapkovaCzechs

Fading Letters Reveal Family's Holocaust Story

Growing up in the safety of Britain, Jonathan Wittenberg was deeply aware of his legacy as the child of refugees from Nazi Germany. Yet, like so many others there is much he failed to ask while those who could have answered his questions were still alive.

After burying their aunt Steffi in the ancient Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, Jonathan, now a rabbi, accompanies his cousin Michal as she begins to clear the flat in Jerusalem where the family have lived since fleeing Germany in the 1930s. Inside an old suitcase abandoned on the balcony they discover a linen bag containing a bundle of letters left untouched for decades. Jonathan’s attention is immediately captivated as he tries to decipher the faded writing on the long-forgotten letters.

Written mostly in German and dated primarily between 1938 and 1939, the letters chart the struggle of Jonathan's great-aunt Sophie, who resided in Czechoslovakia with a wealthy Czech nationalist, but was receiving the letters while visiting the rest of the family Palestine. The letters warn Sophie not to return, but according to Jonathan's father "she wouldn't hear of it," thus sealing her fate.

Jonathan has written a book about his family's story called 'My Dear Ones': One Family and the Final Solution, published by William Collins.